Noble Bairns and Prize Chile

In my family’s New York City basement next to the boiler room where my childhood nightmare Choo Choo lived part time, there was a 5 foot tall wooden bookcase with a scrabble letter O and a teacher’s coffee cup with stacks and stacks of stacks of Rackham Royal Yellow magazines.

Each issue was a portal to another world demanding exploration. There was nature to observe, civilizations to investigate, cultures to understand, and people to know. Fifty lifetimes stood stacked before me on those hallowed shelves, and I had an hour. I had to hurry before winter darkness settled or before the 400 ton, 11 car train returned to “This is the LAST STOP”, our basement boiler room. The boiler exhaled with a deep, guttural, dragon breath that lit the flame in one sweeping shot. Between the possibility of dragon boilers and roaring MTA F trains, the risk was great. Dad needed to up the homeowner’s insurance.

Curiosity was greater. I grabbed a stack and thumbed through it rapidly page after page. Elephants burst into camera frames with ears extended and tusks thrusted, trunk trumpeting, one step before a full-out charge; Kayan women of northern Thailand with heads imperially and impossibly floating above tightly wrapped coils of gold looked curiously at me wincingly looking at them.

Photo by Eye of Science Tardigrade. Scientific Name: Paramacrobiotus craterlaki from the Phylum Tardigrada. Name on the street Water Bear, Moss piglet. Size: 0.5 millimeter. Can survive freezing to -328 degrees Fahrenheit. Can go without food for 30 years. He then becomes Hangry Bear. ;-)

Microscopic tardigrade, magnified 500 times, made me dry heave at such detailed, disgusting, folded, alien, faceless worm pig, Jabba The Hutt ugliness, while on the next page, between battered buildings in “Da Bronx”, scrawled walls carry tags of gangs. Sneakers, hang over laced on crisscrossing wires stumble into the wind. Little girls feint and pivot to jump and stomp between swirling double Dutch ropes, as the youth men bippity bop down the street, boom box on the shoulder, throbbing bass, no treble, while abuelitas and grammas scream: “Turn your radio down, boy!”

Lauren Hill’s soulful silky words ring: “I grew up on Hip Hop.”

I was in high school now, trying to find my voice- my voice on paper, my voice inside and outside. The basement was no longer a portal of dragons, monsters, and trains but a warm haven of peace with palpating heat pumping into the room from the warm breaths of boiler action. I returned to the time machine and pulled out the next destination. It was October 1973, Chile. A young woman, complexion mixed with alabaster, ivory, and cola de mono, squid ink-black straight hair and dark, flaring Latin eyes appeared on the cover. She had a tangelo polo shirt buttoned down, a black, polka dot scarf gently tied around her neck as a choker neckerchief, modestly breaking up the space between what was opened and what was closed. She was a classy Audrey Hepburn or a raw campesina - a country, revolutionary girl. She clasped a stick with a red and white flag attached and wrapped by string. She was simple, young, political, and powerful. She was a “Hija de Chile.” (Daughter of Chile)

I swiped left, rifling page after page, scanning text to find photographs and, when found, vacuuming every color, character, stance, object, geographical landmark and location to return another time for a slow read. This time I was a spy, not a young time traveling historian. I collected data before the doors closed, alarms sounded, and assassins busted in with guns drawn. I was near the end of the download, one last file; I froze at one faded, glitch and grunge, slightly creased, poignant capture. My hand froze on the opposite page to keep the magazine open.

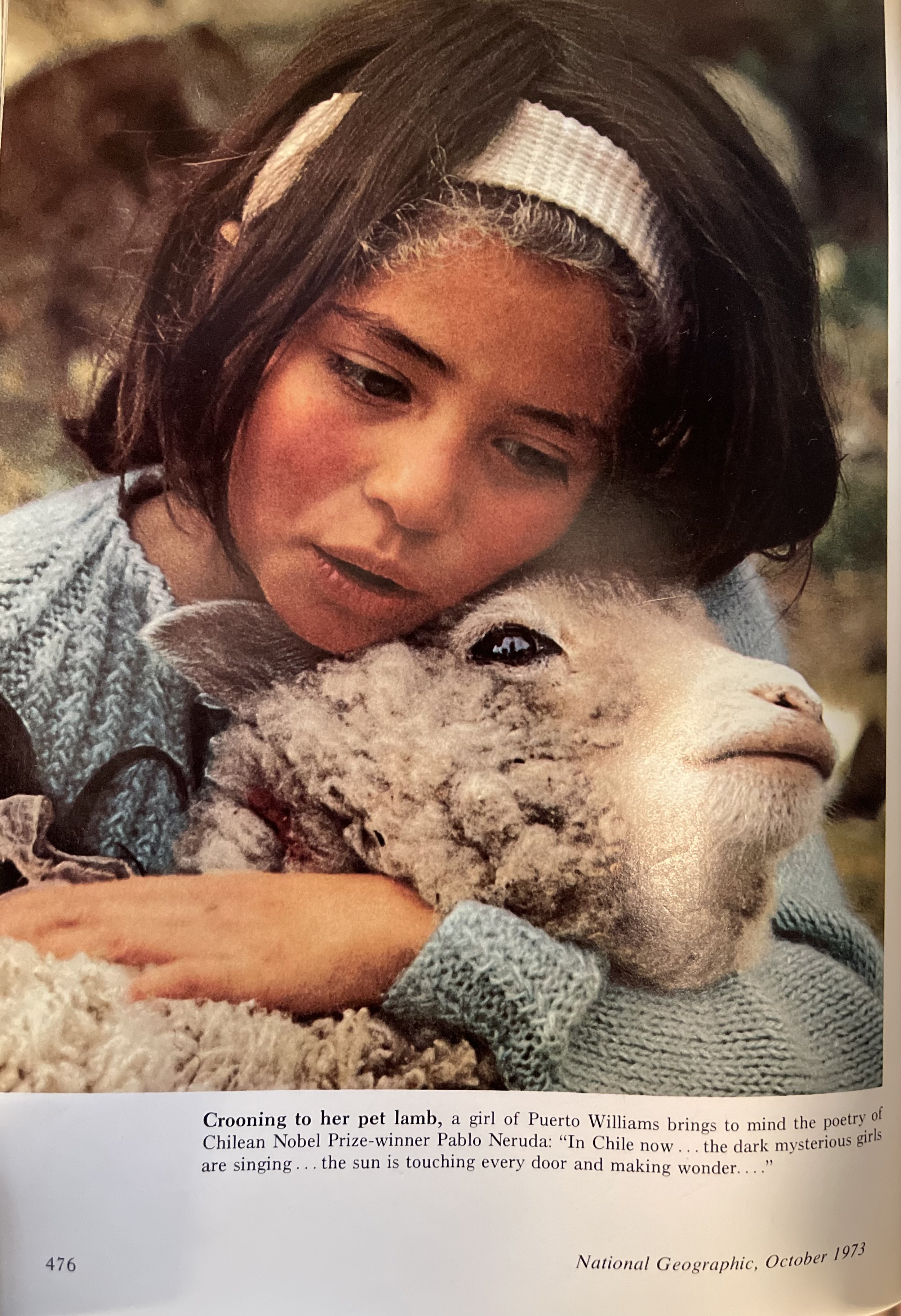

As beguiling as the “hija de la revolución” cover girl was in her post pubescence, so was the serenity of the “chica de campo” (country girl) in this captivating moment. It was a supreme attempt to define a complex Chile. Was it a hark back to an innocent nursery rhyme or was it a spiritual reference of a young king in waiting when Israel was a child, and he had a flock? It was simply a girl and a lamb. She cradled the lamb under her chin. Her chapped lips were pursed while crooning a little canción:

Photo by @kyleincpt

Thanks to life, which has given me so much.

It gave me two beams of light, that when opened,

Can perfectly distinguish black from white

And in the sky above, her starry backdrop,

And from within the multitude the one that I love.

Thanks to life, which has given me so much.

It gave me an ear that, in all of its width

Records— night and day—crickets and canaries,

Hammers and turbines and bricks and storms,

And the tender voice of my beloved.

Photo by @kravitskiy

Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto

Me dio dos luceros, que cuando los abro,

Perfecto distingo lo negro del blanco

Y en el alto cielo su fondo estrellado

Y en las multitudes el hombre que yo amo

Gracias a la vida que me ha dado tanto

Me ha dado el oído que en todo su ancho

Graba noche y día, grillos y canarios,

Martillos, turbinas, ladridos, chubascos,

Y la voz tan tierna de mi bien amado

Her pink skin was weathered by Antarctic winds and a touch of the end and tip of South American sun. She was lost in thought, bundled in an aqua knitted sweater. A cream-colored, crocheted bandana separated her straight, brunette hair from the silver streaks sprouting on the beginning of her crown. Too soon for a little girl from Puerto Williams with one handcrafted doll and named animals. She cradled the lamb like Mary cradled the Christ.

She was no rogue; she probably faced a storm, or maybe she was a Storm. Was it chores before dawn? Egg collection? 5 am milkings? Loss of loved ones? School and Work? Work and school? Life was heavy for Chile in 1973 - inflations and expectations and frustrations and negotiations and shortages and sanctions and factions and fractions and redactions and strikes and no likes and no rights and no rice and debts and threats and regrets and stockades and blockades and blown aids and smoke haze and news and reviews and who’s who’s and loose screws and short fuse and coups brewed.

Last Words [Ultimas palabras] The last speech of the president.

I did not know this history then. Below the photograph, at the bottom of page 476, below the distress and peace, upheaval and tranquility, a child and a lamb, two sentences, eighteen words that changed the trajectory of my voice, writing and life. This was my introduction to the man, Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto, who gave me permission to effuse over the simple, celebrate the nothing, detail the vague, dissect the complex, taste the bland, use copiously “metaphores”, and, when you speak to a beautiful woman, remember more than just her first name and her last.

The superscript simply said:

Crooning to her pet lamb, a girl of Puerto Williams brings to mind the poetry of Chilean Nobel Prize Winner:

“In Chile now…the dark mysterious girls are singing…

The sun is touching every door and making wonder…”

I visited my second haven the next day, Barnes and Noble, downtown Manhattan; fresh printed paper wafted into my nostrils. I was bursting with joy. I walked up to the Book Barista with my discovery, a little uncertain if she knew of this secret hidden in Spanish.

“Hi, I’m looking for a particular author.”

She asked: “Who?”

I replied: “I’m not sure if you’ve heard of him, his name is Pablo Neruda.”

She smiled: “Of course. Follow me.”

I followed her past Science Fiction, Cookbooks, Romance, and Children to Poetry. And there on a dark wood, 8 foot tall bookcase were shelves and eternal rows of Pablo! I picked out one gray book for the grey day. The title was: “The Captains Verses”. I flipped open a page and read:

“Take bread away from me, if you wish, take air away, but

Do not take from me your laughter...””

I looked over to the Spanish original translation on the opposite side of the page while thinking: “My goodness gracious! If English is firing and inspiring me, if only I spoke and understood Spanish, the language of God a German colleague once told me. It read:

“Quitame el pan, si quieres,

Quitame el aire,

pero No me quites tu risa…”

Thank you, Mom and Dad, for making books like candy in our house, and making the “Good Book” the staple. I remember brown, cellophane-wrapped Watchtower and Awake magazines coming in monthly and I will never forget when, every month, a plane ticket arrived to take me to any and every destination on earth in a plastic-wrapped, jonquil-yellow magazine National Geographic that was too sacred to throw away that they moved from the mail slot to the coffee table, to the floor, to the basement bookcase right before they went to the closet archives where I met one evening the Captain, The Senator, The Revolutionary, The Outcast, the 1971 Nobel Prize Winner In Literature and writer of “Ode to the Onion…You make us cry without hurting us.”

Since 1901, The Nobel Prizes have been presented to the laureates on 10th of December, the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death.

Is there a poet, poetry, or quote that has inspired you, or changed the trajectory of your thinking? Comment below.

Photo by Annie Spratt @anniespratt